When the early white mariners from England and France first came on the Maine coast in the early 1600s with some explorer a fisherman before that, they found numbers of Indians living here. In a fairly short period of years, Southern New England Indians were greatly decimated by European contagious diseases to which they had no resistance; this epidemic did not take hold in Maine.

But even today there are descendants of these early Indians living in Maine and Canada and in other parts of the country where they have gone to live. Also there is a considerable amount of Indian blood in families that know nothing of it or that make no point of it; these family genealogies have not been carefully worked out.

Sometimes it is only a single person, as in the Ellis family who have an Indian woman in their 18th century background, apparently a Massachusetts coast Indian woman who had a very long life. Any appearance has totally faded out in her descendants, but at the turn of this century the older members of the family still show the Indian blood.

So the Indians that the early explorers first saw here can be known as historic Indians, those that lived here several thousand years ago, the so-called Red Paint Indians, are prehistoric and relatively little is known about them. Only from their artifacts can conclusions be formed, artifacts deposited in their graves.

However, archaeologists working here since the Second World War seem to indicate that the Red Paints occupied part of Maine about 1500 to 2000 years B. C., about 3500 to 4000 years ago. If the radioactive carbon 14 system of dating, developed after the Second War, had been known to Charles Willoughby of Harvard, the first true archaeologist to explore here, he would have been able to ascertain close dates for the Red Paints.

He was able to find some bone and bark fragments in the cemeteries where these Indians buried their dead with red ochre; something with carbon residue must be utilized in the testing. When Warren Moorehead, an early American Indian archaeologist, from Phillips-Andover School in Massachusetts, made his archaeological survey of Maine in the years 1912-1920, he excavated numbers of Red Paine Indian grave sites. He would learn about these from persons digging cellar holes, deep plowing, or from some other excavation.

When Moorehead systematically excavated and studied the remains, he would find fine tools accompanied with red ochre in the graves almost invariably. This led on to the term Red Paint being applied to these early Indians of Maine and nearby regions.

About 1920 the Moorehead party came to Oakland and excavated the Indian cemetery near the railroad overpass leading into the town from the west. According to John Franklin Hill (1886-1980), who was an amateur Indian archaeologist himself, and was the Model T Ford agent in Waterville at the time. Moorehead had a tent and placed a number of his uncovered artifacts on exhibit therein. Most of the artifacts from Oakland went to the Wilson Museum in Castine.

It may have been about this time (1920-) that his party came into Belgrade and accrued Luville Cook (1898-1967) to guide them about the lakes; from what Luville had been told by Amos Furbish, a much older local man, he was able to lead the Moorehead party to one or more Indian camp sites.

The compiler about 1949 found his interest excited in places where Indians might have camped in the Belgrades; he was able to locate a few of these places and examined them in some detail. The Indians would place in their wigwams a submerged pit rocked up with stone, for a small fire. Because of the building of dams at the outlet of our lakes by the earliest settlers, most of the Indian campgrounds were flooded by 1800, it was fairly easy to locate underwater the discolored piles of stones that had once boxed a fire pit.

The Indian arrow heads he found seemed to have been made on site, as the small flakes from the flint could be seen in the sand. He found a few scrapers of axe heads of stone that showed the grinding marks on the edge. His most remarkable find were the remains of Indian-made clay pots. They consisted of a large number of pieces of more than one pot with decorations visibly impressed around the top edges. For a long time he was baffled in finding black on the inside curve, not the outside, as it seemed to him it should be if they were used for cooking.

He later found that when the Indians made these pots from local clay, they air dried them sufficiently to hold together; then they turned them upside down and baked them over a small fire. That explained why the black was on the inside of the curve of the fairly small pieces that he located on a Belgrade lakes campground. These clay pots seem to have been the only ones ever discovered in the Belgrades. The Moorehead party almost certainly never saw this particular campsite, as it was probably flooded when they came here in 1920.

So from our own observation we know that the historic Indians camped around the Belgrades in a number of places, that they knew how to make hunting and domestic tools, and they knew how to decorate them. They understood the best and most sensible method of making a firepit in their wigwam for cooking and heating. And they had tools for working skins of deer and moose and other animals. They could not have been around the lakes without the knowledge of making a bark canoe, the materials for which they could easily find in their time.

Not as much is known about the prehistoric Red Paints; they buried their fine gouges with their dead. We believe that the artifacts that have been found on the surface in various parts of Maine, were made by the historic Indians and their forefathers. Occasionally there is an exception. Ernest “Buster” Cook once found many years ago what was clearly a Red Paint artifact on Cook’s Beach on Horse Point; they had been there several thousands of years before. The compiler in 1949 found a hole and pendant on Messalonskee that was probably Red Paint.

When it comes to the finer details of how the Indians of the Belgrades lived before white settlement, we must depend on Frank Speck and Fannie Hardy Eckstrom, lifelong anthropologists, who early in this century visited and even lived with the Penobscot Indians at Old Town to learn from them all of the old ways of Indian living.

All of the Indians that once inhabited the Belgrades had their ancestors in Asia; when the oceans were much lower than they are now a land bridge appeared between Siberia and Alaska. This made it possible for humans and animals to pass from Asia to this uninhabited hemisphere. This is supposed to have happened years ago.

When the white settlers first came into this town in the 1770s no Indians then lived here. The Indian massacre at Norridgewock in 1724 had driven or frightened away the Kennebec Indians, for the most part. The survivors of the 1724 attack went through the woods to the St. Lawrence and appeared across the river from Quebec requesting assistance. They later went to St. Francis. A few of them may have joined other Maine tribes.

Occasionally, down into the last century, nomadic parties of the descendants of the Kennebec Indians would be seen on the Kennebec River. It is not believed that they ever returned to the Belgrades. But as late as 1753 the Kennebec proprietors found it necessary to treaty with Norridgewock Indians over land claims on the Kennebec River.

Francis Parkman (1823-1893) spent his life in writing his great history of this succession of conflicts, when the Maine frontier was all afire. For some reason unknown to us, Maine’s long and terrible experience in the hundred years of conflict has not become a part of the national popular historical culture. This has centered on events west of the Mississippi, an experience of much shorter duration. Only the interested student of local history in Maine will ever find much about our prolonged white and Indian conflict, with atrocities on both sides.

This conflict reached a point where some whites would systematically hunt and shoot Indians found in the woods, as they would a black bear. This might trace back to the wife or family member of such a hunter having been killed by Indians at some earlier date. Ben Pine on the coast of Maine was such an Indian killer, as was of Newcastle.

The Indians committed atrocities, especially on their prisoners. John Gyles, who was captured at Pemaquid in 1689 and held by the Malecite Indians on the St. John for many years, later wrote his memoirs and described the cruelties to which the Indians subjected their captives.

Probably the most cruel Indian in Maine history was the terrible Asacumbuit. He became so famous among the French that they sent him to France where this sadistic killer claimed to Louis XIV that he had killed 300 people with his own hands; of course this might have been an exaggeration. At one time Asacumbuit was holding a young girl prisoner at Farmington Falls, where he would occasionally strike at her; apparently, he enjoyed her screams.

After the end of this conflict Indians no longer had support from the French to the north. They became a kind of nothing class of people subject to attack in their camps by white renegades. John Neptune, a famous Penobscot chief, was trapping out of his camp on Lake Moxie above Bingham in 1830s. During one of his absences, whites stole his great catch of furs and burned his cabin.

Although there were European fishermen off our coast in the later 1500s, the century from 1600 to 1700 is epochal for our Maine Indians. At some date around the beginning of this period they saw the first white men’s track on the beach and were as astonished at the differences from their own moccasin imprint that they were still talking about it 300 years later.

They had several ways of making or obtaining fire. They knew the spindle method and they sometimes found fire where lightning had struck a still smoldering tree. They carried fire on their long treks in a quahog shell lined with blue clay. Yellow birch punk carried inside this container would be ignited; this they could carry for many hours.

When the whites first came on these shores before and after 1600, it was to the advantage of both parties to engage in friendly trade and explore their diverse cultures; the whites learned a great deal from the Indians and the reverse was true. By the middle of the century the Indians were well acquainted with firearms and traded furs, iron pots, and other objects and for cloth.

A number of trading posts were established on the Kennebec, at Clark & Lake at Ticonic (Waterville) establishment on Arrowsic Island, at Augusta, and other places. Besides these permanent establishments, the occasional trading boat would come in the River to deal with the Indians. From time-to-time even in the earlier decades, there were hostile incidents and events. It was not until King Philip’s war in the 1670s that the war path was generally resorted to by Maine Indians. A combination of local international factors now led on to nearly 100 years of war, War in Europe between the French and English, with French Quebec to the north and the English colonies to the south, the intrusion of English white settlers upon Indian lands, the supply center at Quebec made available to them, ransom money as a reward for surrendering prisoners, all led on from King Philip.

By the remaining groups of rocks from their fires, it has been possible to find in the Belgrades a limited number of localities where the Indians set their wigwams. Apparently, in historic times, our Indians had no permanent camps in this locality. Their temporary shelters were constructed of four poles tied together at the top, with the bottom set out in a square about ten to 12 feet apart.

The walls were covered with bark. The hole at the apex of the pyramidal structure let out the smoke from their fire. Our Indians appear to have been transient and may have spent the winter in Norridgewock or other places. About 1706, carpenters came up from Boston and built permanent and comfortable houses at Norridgewock called “Moss houses,” probably so-called using moss for chinking between the logs. These were the structures they were living in at the time of the massacre in 1724.

When the whites first came here, they found that the Indians had invented a device for winter travel on deep snow, the snowshoe. An Indian snowshoe can be identified by the fineness of its weave. They wove the rawhide closer together than the whites, and this can be noticed in museums where their snowshoes are on display.

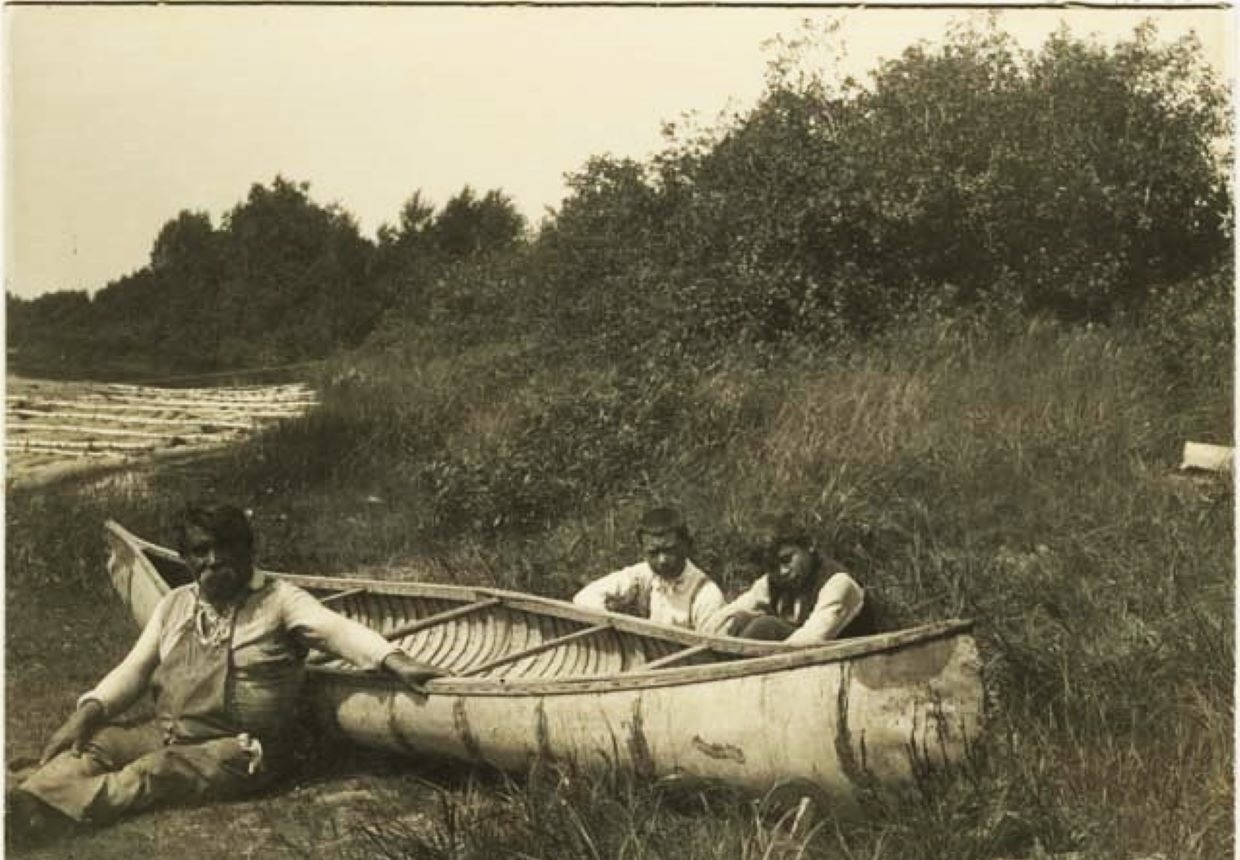

For summer travel they had invented the birch bark canoe. When our own amateur Indian archaeologist, John Franklin Hill, was a young boy, living on Chebeague Island in Casco Bay, in the 1890s, the Passamaquoddy Indians came there in the summer and lived in tents, selling their handicrafts to summer people. John became acquainted with them and made Indians and their remains a lifelong hobby; his collections were given to the Bates Museum at Good Will Home, and a Hill Memorial Room has recently been established there. As late as the 1960s, John was corresponding with an aged Passamaquoddy woman on the method of making a birch bark canoe.

When Edward E. Bourne wrote and published his history of Wells in 1875, partly based on his father’s researches earlier in the century, he was able to describe the relationships, friendly and hostile, of the settlers and the Indians. When the local Indians were in a friendly mode they would place their wigwams near the garrison houses in Wells.

Nearby their wigwams they would set up a pile of rocks. According to Bourne, when they planned to leave and go on the warpath, they would always signal their intent by taking down the pile of rocks. Because they had no system of logistics, their campaigns were of short duration, a few weeks. But during this time they could burn buildings and scalp settlers and kill settlers and take prisoners.

Wells was the eastern bastion of the New England settlers. In their desperation swift couriers would be sent to Boston requesting medical supplies, armed men and supplies to assist in holding out. “Everything has gone east of Wells,” they would report. “Rally to us now.” These noble defenders are little remembered today.

This history is attribute to, yet not confirmed to be written by Sturtevant