The history of Belgrade, Maine, offers a rich narrative spanning its early settlement, evolution into a thriving agrarian society, and subsequent industrial endeavors.

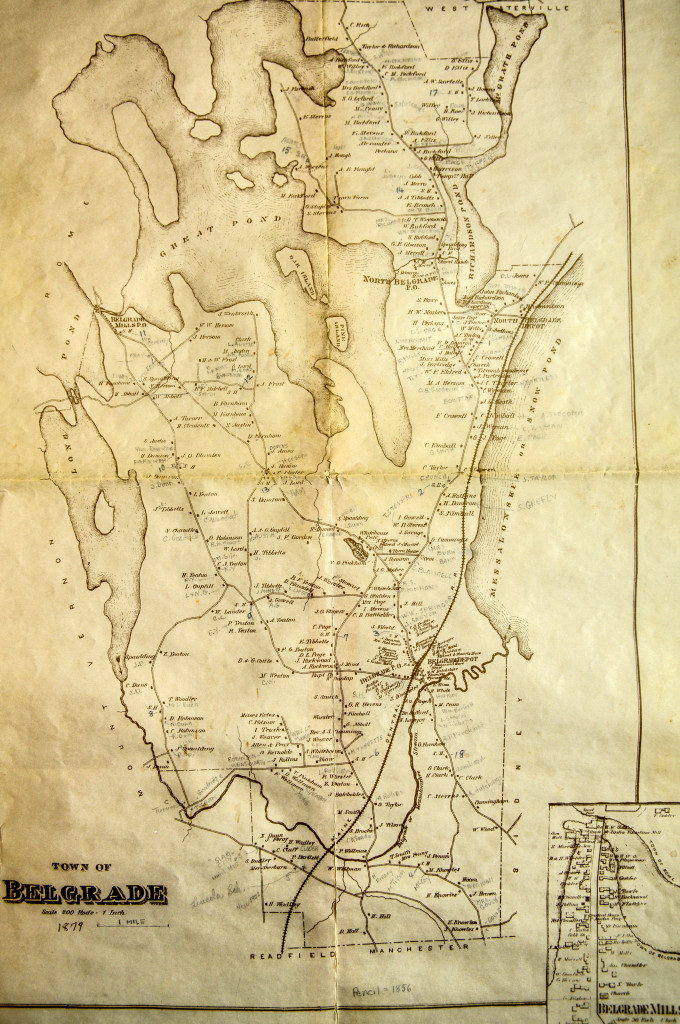

Belgrade grew from a scattered frontier settlement into a town shaped by three closely connected but distinct centers of life: North Belgrade, Belgrade Depot, and Belgrade Lakes Village. The earliest farms took root in North Belgrade around Belgrade Hill, where families like the Wymans, Snow, Richardson, and Yeatons cleared land, built stone walls, and created a tight-knit agrarian community that remained the town’s farming heart well into the 19th century. With the arrival of the Maine Central Railroad in 1849, Belgrade Depot became the town’s commercial and civic hub—home to mills, stores, the Grange, and later the meeting place for town government—linking local farmers to wider markets and bringing new energy to daily life. Meanwhile, Belgrade Lakes Village evolved into the town’s waterfront gateway, first as a mill center known as Belgrade Mills and later, after 1900, as the celebrated summer resort of “Belgrade Lakes,” drawing hotels, camps, cottages, and generations of visitors who made the lakes famous through fishing, boating, and the enduring lore of places like Snug Harbor and the mail boat.

Early Settlers

Before 1800, few explored the area we now know as Belgrade, a land inhabited by Native Americans of the Abenaki tribe. The region, initially part of the western edge of the Kennebec Purchase, was known as Washington Plantation. The Kennebec Proprietors’ lots were being sold, and some men had money to buy land. Others were veterans of the American Revolution claiming their recompense. Some did not have the cash but came anyway. They “settled up” later when the Proprietors in Boston offered a low price to “quiet” the squatters, who had no deeds.

The known history of Belgrade began in 1774 when Philip Snow ventured beyond the familiar lands in Sidney. He built a log cabin about two miles north of what is now Belgrade Depot and used it as a base for hunting expeditions. In time, Snow sold the cabin to Joseph Greely and later settled on the west side of the lake with his wife and nine children. Snow Pond (now Messalonskee Lake) and Mt. Philip were named in his honor.

Later that year, two other settlers crossed to the west side of the lake to take up permanent residence. The first was Simeon Wyman, who with his wife, Thankful, and six children settled on the southern slope of Belgrade Hill. He cleared the first farm in the new area. Later, the Wyman’s son, also named Simeon, was the first white child to be born on the west side of the lake.

The second new arrival was twenty-four-year-old Joel Richardson. He was not married, and he settled on the north slope of Belgrade Hill. Two years later, he married a Wyman daughter named Sarah.

Another early arrival was Paul Yeaton, coming to Belgrade in 1794. He was a Revolutionary War veteran who built his family homestead on the West Road. He introduced a surname that came to be represented by many residents through the 20th century.

That same year, Simeon Wyman and his family cleared the first farm on Belgrade Hill, becoming the area’s first permanent settlers. Joel Richardson and Paul Yeaton, along with numerous other settlers bearing names like Bean, Crosby, and Staples, followed shortly thereafter.

Other early settlers’ names included Bean, Blake, Crosby, Crowell, Fall, Gilman, Hall, Hemmingway, Leighton, Linnell, McGrath, Mosher, Page, Philbrick, Rankins, Richmond, Staples, Taylor, Tilton, Tozier, and Weston. While some of the family names of these early settlers still exist in Belgrade, many no longer exist locally.

Becoming a Town

Belgrade was incorporated in Lincoln County in 1796 as a town of about 250 inhabitants, which was considered a large town in those days. The area, first called Washington Plantation, lay at the western edge of the Kennebec Purchase.

Later that year, a small part of Sidney, the land lying between Belgrade Hill and Oakland on the west side of Messalonskee Lake, was annexed to Belgrade by consent of the General Court.

A second acquisition of territory to Belgrade came later. The residents of the Town of Dearborn, incorporated in 1812 when it was known as West Pond Plantation, petitioned the Maine Legislature to be divided and annexed to neighboring towns. An act was passed in 1839 dividing Dearborn among the towns of Belgrade, Waterville and Smithfield. The land added to Belgrade lay north of the North Belgrade Stream up to the present Smithfield border. It constituted about one fifth of the area of Belgrade, adding about three hundred people to Belgrade’s population and making the size of Belgrade what it is today.

About two years later, the residents of a large part of Rome also petitioned the Maine Legislature to become part of Belgrade. This petition, however, was turned down.

Town Government

Belgrade’s first town meetings were held in private dwellings or taverns since Belgrade did not have a town hall. Finally, in 1814, two hundred dollars was set aside to construct a building for town meetings. Beginning in 1815, town meetings were held at the Old Town Meeting House on Cemetery Road. When a Native American ill with smallpox in 1834, he was quarantined in the building, and a frightened community shunned it for future gatherings. In 1872, town meetings were moved to the Masonic Hall at Belgrade Depot, which later became the Grange Hall. In 1962, meetings were again moved to the Central School gymnasium. Beginning in 2001, town meetings were moved to the newly built Belgrade Community Center for All Seasons, just north of Belgrade Lakes Village. The Old Town Meeting House was renovated in 2023 and is under the stewardship of the Belgrade Historical Society, and an application to be a registered historical landmark is pending.

Belgrade’s 1815 Old Town Meeting House

In the early years, Belgrade did not have a town office, but had for its “office” a trunk containing town records that was kept by each First Selectman, in whose home meetings were held. Later, one room in the first Central School became the town office, but in the tragic fire that destroyed the school in 1943, all the town records were lost. A room in the new Central school was used until 1960, when the town office moved to the back room of the Belgrade Lakes firehouse. Finally, in 1969, the town office was moved to its present location at the southwest corner of the intersection of Routes 135 and 27 adjacent to the gravel pit.

Belgrade Farms

Almost all early Belgrade residents were farmers. Before the coming of the Maine Central Railroad in 1849, each family or cluster of farms was self-sufficient, clearing their land and raising their own crops and livestock. Sheep became especially important Sheep’s wool increasingly yielded to the Jersey cow’s milk as a cash crop.

The Rockwood Farm across from the Old South Church

Agrarian Roots

Belgrade’s economy throughout the 19th century was primarily agricultural. Almost all early families cleared their land and raised crops and livestock to sustain themselves. Sheep’s wool was especially vital locally in the first half of the 19th century, first for home use and then for the woolen mills. Later dairy farming, particularly with Jersey cows, became a more prominent cash crop. In the mid-1800s, horses began to replace oxen for farm work and travel. Farming was hard work, and large families to share the burden of farm labor were common. Census records show that quite often extended families lived together on Belgrade’s farms.

The arrival of the Maine Central Railroad in 1849 transformed farming practices by enabling farmers to ship goods such as apples, potatoes, and corn to distant markets.

The Maine Central Railroad first came to Belgrade in 1849, allowing farmers to ship their products to market and making Belgrade’s lakes a tourist destination.

Belgrade residents became increasingly prosperous during the 19th century. There were several gristmills in town to grind the corn, wheat, and other grains raised by local farmers, and extensive logging made for a number of sawmills in operation. When staple crops such as corn, potatoes and apples could be shipped to faraway markets by rail, farmers received cash for their produce. Maine apples were always in demand, many being shipped to other states and to Europe, where Maine apples brought the highest price of any in the United States.

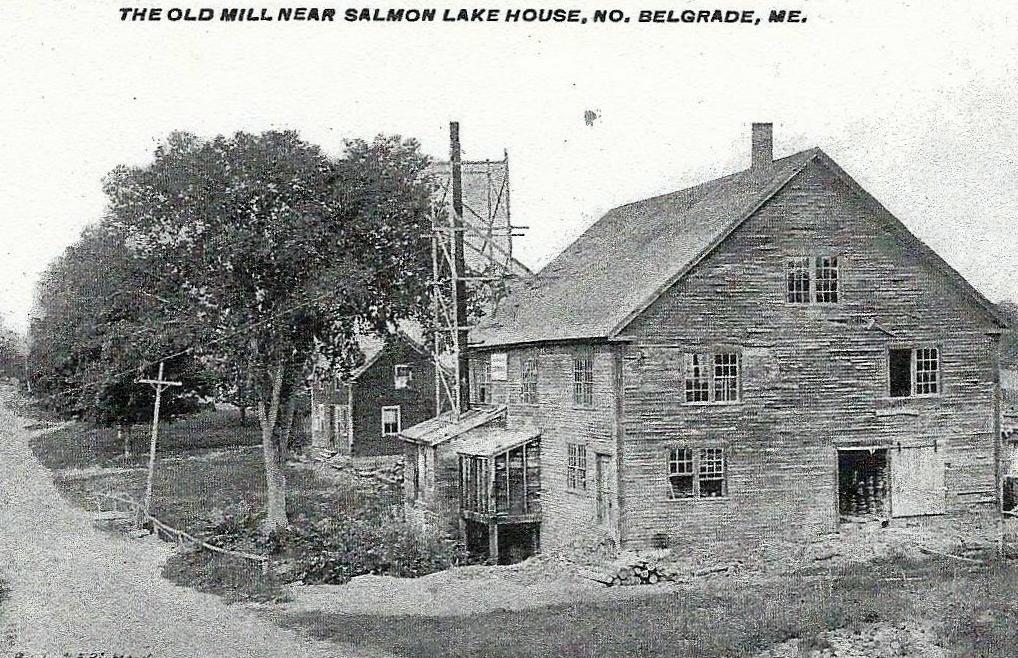

Large numbers of barrels and boxes were required to ship Belgrade’s apples, potatoes and corn to market. William Withers operated a mill near the dam in North Belgrade that produced barrels for farmers.

The Granges

Nothing brought Belgrade people together more than their chapters of the Patrons of Husbandry, commonly called the Grange. The Belgrade Grange at the depot was originally organized in 1887. It was a center for social interaction, yet its primary mission was to support agriculture in the town, supporting farmers through fairs and gatherings. These community organizations embodied the town’s agrarian spirit.

A second Grange was organized in 1906, when the Salmon Lake Grange in North Belgrade was chartered. Over the years, Salmon Lake Grange sponsored several fairs which included horse pulling, while the Belgrade Grange at the Depot and the Ladies Aid had indoor fairs with a supper. The Salmon Lake Grange Hall fell into disrepair and burned, and sadly we have no extant photograph of the building.

The Belgrade Grange Hall in the Depot was used for many community events.

Industrial Development

The history of manufacturing in Belgrade reflects its transition from a primarily agrarian society to one that embraced small-scale industry. The town’s forests and waterways played a crucial role, supplying materials and power sources for early industries.

During the 19th century, sawmills and lumber operations flourished, relying on waterpower from local streams and lakes to process timber into lumber and shingles. Other cottage industries emerged, including artisan workshops producing textiles, tools, and agricultural implements. Families often combined farming with craftsmanship to sustain their livelihood.

At one time Belgrade Lakes was known as Belgrade Mills and Chandler’s Mills.

In 1888, Belgrade’s industrial activity included Henry W. Golder’s spool factory, employing 18 men, as well as Everett Cummings’ rake handle factory, Henry Morrill’s grist mill, and the Soule and Austin excelsior mill. The abundance of waterpower in Belgrade Lakes led the area to be known as Belgrade Mills or Chandler’s Mills. A store owned by T.S. Golder was reportedly the largest store in Kennebec County. One could purchase a wide range of items from a fine-tooth comb to a bag of meal.

However, advances in transportation and industrialization in urban centers led to the decline of local manufacturing by the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The town’s economy subsequently shifted toward agriculture, tourism, and recreational services centered around the Belgrade Lakes.

Pine Grove Cemetery

Belgrade cemeteries

The earliest burial in Belgrade was in Pine Grove Cemetery, on the south side of Route 135, in 1803. Across the road, near the intersection with Route 27, is Woodside Cemetery, where the first recorded burial occurred in 1812. The next year, second-settler Joel Richardson was also buried there. The two other Belgrade cemeteries are the Quaker burying Ground, just to the east of Pine Grove Cemetery, and Ellis Pond Cemetery, just off the west shore of Salmon Lake. Peaseley Morrill, the father of Belgrade’s two governors, was buried there in 1855.

Tourism in Belgrade

Following the Civil War, the railroad emerged as an essential asset to the town of Belgrade for decades, serving not only as a means for transporting agricultural goods but also supporting broader economic and community growth including tourism.

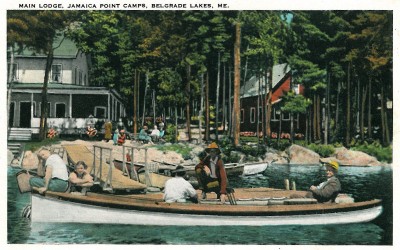

The emergence of an affluent upper-middle class was eager to escape the noise and pollution in American cities by getting back to nature, and many of these “rusticators” found the Belgrade lakes a welcoming summertime destination. Charles Hill, the proprietor of the Belgrade Hotel succeeded in lobbying to change the name of the village to Belgrade Lakes, to appeal to tourists. Fishermen led the charge, but in 1900 the Belgrade Hotel was built to entice visitors to vacation in elegance by the clear water of Long Lake. The hotel complemented the many inns and more rustic lodgings around the lakes.

The Belgrade Hotel, built in 1900, was the jewel in the crown of the Belgrade lodging establishments.

At the same time, the number of new cottages and summer youth camps in Belgrade was exploding. Many more Americans owned automobiles, which brought hordes of tourists to the lakes. Over one hundred businesses eventually joined the list of accommodations in the decades prior to World War II. Only the Village Inn, originally the Locust House, currently remains of the former hotels/inns. The truck farms that sustained the original hotels and camps with a central dining room are also long gone.

Camp Merryweather, located on Great Pond in North Belgrade, was founded in 1900 by Henry “Skipper” Richards and his wife, Laura Richards, making it the third oldest boys’ camp in the nation. Mrs. Richards was the daughter of the composer of The Battle Hymn of the Republic, Julia Ward Howe. Among the boys who attended the camp were the sons of President Theodore Roosevelt, Admiral Hinds, the poet Conrad Aiken, and Laurence Rockefeller. Camp Merryweather continued in operation until 1937 and is now a private residence of the founding family.

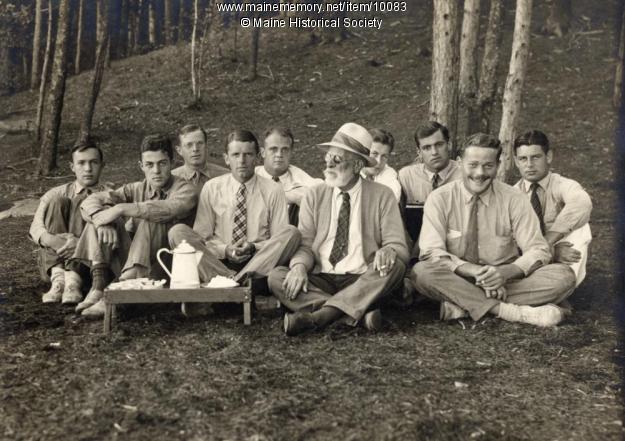

Henry Richards and his camp counselors taking tea at Camp Merryweather.

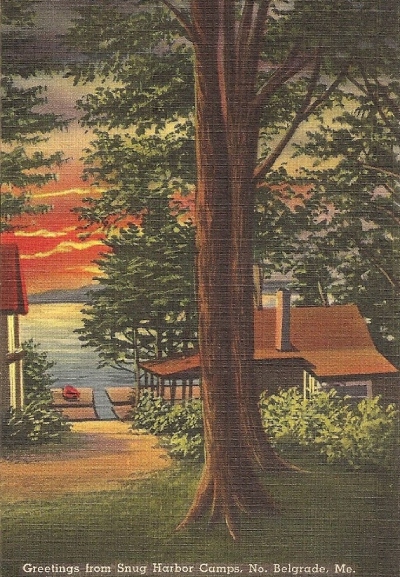

The noted author, E.B. White, came to Snug Harbor Camps on Great Pond with his family in 1905 for a stay he described later in his life as, “four solid weeks of heaven.” His essay, “Once More to the Lake“, first published in Harper’s Magazine in 1941 chronicles his pilgrimage back to Snug Harbor with his son. A quote from the essay is featured on a memorial bench located on the Village Green near the gazebo.

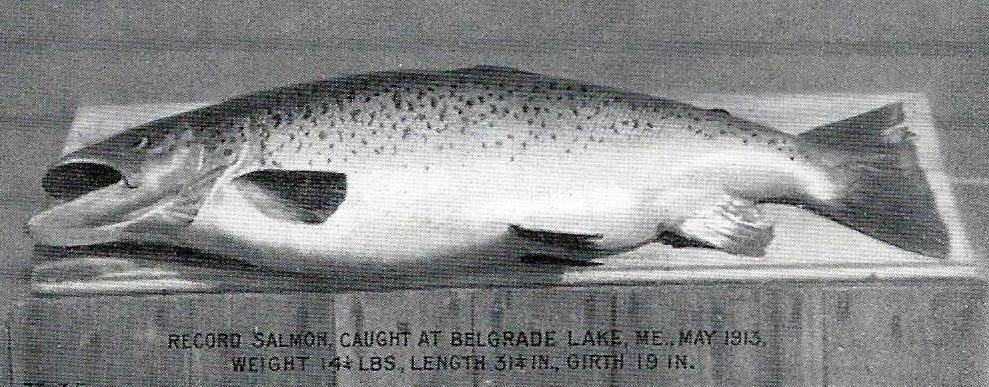

Record Salmon caught May 1913 – 14 1/4 pounds

A prize winning salmon

Waterville Morning Sentinel – December 18, 1913:

“Belgrade has the honor of producing the largest land-locked salmon in the United States during the past year. In May last, Rev. Edwin A. White caught the fish, which weighed 14 pounds and four ounces. The salmon, now mounted, adorns Mr. White’s library.”

Based on records of the Maine Dept. of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife, salmon were first introduced into the Belgrade Lakes in 1878. Perhaps this is when the name Ellis Pond, which had formerly been Richardson’s Pond, was changed to Salmon Lake.

A tradition that has been enjoyed by camp owners on Great Pond for many years is the U.S. Mail boat, which has been delivering mail to residents on the lake for over a century. An article from the Waterville Morning Sentinel of April 11, 1905, tells us when: “The official announcement has been made that the government will establish a summer mail route on the Belgrade Lakes.” The mail boat was featured in the 1979 play, On Golden Pond, written by local resident Ernest Thompson. It was later made into the 1981 Academy Award winning movie by the same name starring Katherine Hepburn, Henry Fonda and his daughter Jane.

Guides in Belgrade Lakes, waiting to take their “anglers” out to “wet a line.”

1981 On Golden Pond movie poster

Hundreds of private cottages now crowd the shores of the lakes in Belgrade. A few childrens’ summer camps remain active including Runoia and Pine Island, yet many others have been subdivided. The “Golden Age of Tourism” may have ended, but thousands continue to flock to the lakes in Belgrade every summer, keeping the heritage alive and well.

Legacy and Modern Belgrade

Belgrade’s identity now lies in its community-focused values, historical preservation efforts, and its natural beauty, which continues to attract tourism and recreation centered around the beloved Belgrade Lakes region.

Everyone associated with Belgrade and its lakes should be proud of our rich history, one the Belgrade Historical Society strives to preserve for future generations.

Belgrade: A Landscape Shaped by Stone, Ice, and Water

Belgrade’s quiet lakes and wooded hills feel timeless, but the landscape we see today was shaped by a long and dramatic story that began millions of years before people arrived.

Deep beneath us lies mostly granite, formed far inside the Earth. At different times in the distant past, this land was covered by ancient seas, and the continents slowly drifted into their present positions. Traces of that sea can still be seen in the flat layers of shale around Ellis Pond and Belgrade Hill—rock that later proved perfect for early settlers’ walls and foundations.

The greatest force shaping Belgrade, however, was the last great glacier. About 18,000 years ago, ice more than a mile thick covered Maine. As it slowly melted and retreated, it carved out our lakes, scattered giant boulders across fields, and left long ridges of gravel that later became valuable local resources. Many of our smaller ponds—like Penney, Hamilton, and Stuart—were formed when buried blocks of ice melted and left water-filled hollows behind. You can still see the glacier’s scratches etched into rock ledges around Ellis Pond today.

When people arrived, they built directly from this landscape. Indigenous peoples quarried stone from natural boulders. Early settlers used granite for foundations and shale for walls, creating the iconic stone fences that still lace the countryside. Skilled local craftsmen, especially John and Leslie Damren, split massive boulders into building blocks before concrete was common.

In the 20th century, much of this stone was crushed for road building, and the glacier’s gravel deposits became an important source of work for local contractors after World War II.

Over time, Belgrade also became a place where people connected local life to big ideas about Earth’s history. Residents like Avery Merrow returned from mining in California fascinated by fossils and Darwin’s theories, and Colby professors brought students here in the 1930s to study ancient seashells in local clay pits.

In the end, Belgrade is not just a beautiful lakes town—it is a place where ancient oceans, moving ice, and human ingenuity came together to create the landscape we live in today.

Geological History

When Belgrade was settled in its first pioneer age 1770-1800, nobody knew about the science of geology, or the study of fossils that came to be called paleontology. In the ensuing 200 years these sciences have experienced the highest development and their scholars have created large libraries of books about their theories and findings. In the 1860s and 70s Avery Merrow (1841-1926), who owned the farm in North Belgrade where Roger Bickford now lives, worked in the hard rock mines deep underground in California following out the gold veins. In the deep recesses he found fossil imprints in the quartz rock. According to his son, Ernest Morrill Merrow (1876-1961), in a conversation with the compiler in the 1950s, this led his father to believe “there was something in” the theories of the celebrated Charles Darwin who had recently traced the descent of man to a primate-like creature. The Darwinian theories in that time were hot topics of conversation, and led on to such popular phrases as “man is descended from monkey,” or misconceptions about the “missing link.” Echoes of these ideas could still be heard about town in the 1920s.

In time, as careful and thoughtful scholars in England and Europe commenced to study rocks and the imprints of fossils of plants and animals found in them, they were able to set up a scale of ages and eras that described events in Earth’s prehistory. For the earliest events relating to living things, they refer to a period 2400 million years ago that they entitle Pre-Cambrian, with the Cambrian period going back to only 570 million years. Then things begin to get exciting with the development of sea creatures and simple multiple-celled animals.

With the Jurassic period of 210 million years ago, we get the development of dinosaurs, large reptilian animals. Mud turtles, that we are all familiar with, existed at that time. The dinosaurs existed for many millions of years and the became extinct about 65 million years ago, at the beginning of the so-called Tertiary period. Although no traces of dinosaurs have ever been found in Maine, their track imprints have been found in Connecticut; that is so near to us that it is possible they were wandering here also. An early living shelled creature, called the trilobites, were found in the sedimentary rocks of Fairfield some 50 years ago by Ray Tobey, a native of that town and teacher at Choate School in Connecticut. Tobey was at the time studying for his master’s degree at Clark University under the famous Wallace Atwood, who had written the geography books that we were reading in this town in the 1920s. It is possible that a careful examination of the sedimentary shale layers on the east shore of Ellis Pond would turn up some of these and other fossil traces.

The base rock of Belgrade is mostly granite that the geologists call an igneous rock. On the east side of town, showing up clearly on the east side of Ellis Pond (Salmon Lake), the end of a long finger of sedimentary shale extending from Washington County can be found. This is also evident on Belgrade Hill, where all the stone walls are made of flat rocks and shale. Shale is laid down in layers and was formed at the bottom of the sea that once covered this part of what became Maine; the geologists call this sedimentary rock.

More than 40 years ago the compiler discovered seashells imprinted in fossiliferous rocks around Spauldings Point, on Ellis Pond. He believed these stones were deposited there or nearby by the glaciers that had scraped them off far to the north thousands of years ago. He believed that when the nearby fields were cleared of forest and plowed, the rocks turned up were dumped on the Point shore from drags pulled by oxen. Joseph Merrow (1840-1923), had once owned this farm from the 1870s to the end of his life. When he was a young farmer cultivating the land, he had hired his nephew, Bert Merrow, in the 1880s of the last century, to pick rocks and clean up the fields. It was probably during such a process that the small forsilled fragments, that the compiler discovered in the late 1940s, came to be on the lake shore.

During one of the early periods in Earth’s history, all the landforms came together in one large continent entitled Pangea. This ultimately broke up into the various continents that now exist. The surface of the Earth is now broken up into sections called tectonic plates. As these sometimes move and run against each other, earthquakes occur, as in California recently. In the 1920s the compiler recalls Maine being disturbed by numerous small tremors, so small that there was no fear or consequences from them. Belgrade felt them, that is all.

Glaciers

In much more recent geological time, Canada and this part of America experienced a number of ice ages with the falling snow not melting and forming into ice at the bottom. The last one of these glacial ages saw its height here in Maine about 18,000 years ago and commenced to slowly melt after that. By 12,000 years ago it was withdrawing from our landscape quite speedily. Rivers formed under the ice and sand and gravel and rocks were deposited at various places. There seemed to have been one such river that dropped great deposits of gravel, beginning at Smithfield and passing on to what is now Horse Point, Pine Island, Foster’s Point, the Pine Grove Cemetery area and ending at Summer Haven. From these deposits vast quantities of gravel have been mined, and much money earned by our local small contractors, mostly since the Second World War in 1945; these gravel deposits were little exploited before that time.

The gravel deposits in their several largest areas indicate where the glacial river stopped for a time before again retreating. The glacier at its highest point may have contained a mile of ice over the land. This pressed the land down so that the sea came in upon it as the ice melted; Maine land is still supposed to be lifting from this depression of thousands of years ago. On the south end of the local glacial river is to be found Penney Pond and a number of others in the neighborhood of what is today called Summer Haven. In the pioneer days, and long afterwards into this century, it was called the Moose Yard, probably for the existence of such animals when the settlers first arrived. These steep-sided ponds the glaciologists tell us were formed by blocks of ice breaking off from the main glacier and getting covered with gravel. Hundreds of years may have passed before those blacks melted, and the hollows filled with water to create the ponds that we now see. This is the same way that Hamilton and Stuart ponds were formed. Near the town office other signs of the last glacial passage can be found today. When the compiler joined the local teacher, Raymond Stickney, in the summer of 1936 in the haying crew on the John Damren farm in East Mt. Vernon. Stickney, a Colby educated man, took his young companion out to the Damren pasture one evening (such a crew in those days would board and room in the farmhouse) and scratched away a few inches of topsoil down to the ledge beneath. Here Stickney explained the visible scratches as being those of the last passing glacier of 10,000 or more years before. More scratches are clearly visible on the Jones’ ledge on the east side of Salmon Lake.

The man who first developed the study and understanding of glaciers was the Swiss scholar, Jean Louis Agassiz (1807-1873). Already observer of glacial action in Europe, he came to this country in 1846 where in time, he joined the faculty of Harvard College. He came to Maine in the 1860s and studied the terrain from Bangor to the coast. He may have known something about the Belgrade Lakes, as he made a comment about one region in them at that time.

The rock that underlies Belgrade for the most part, granite, can be seen in its outcroppings on the top of Mount Philip in Rome, on French’s Mountain in Rome, at Mount Dodlin in Norridgewock, on the side of the Long Narrows Road to Castle Island, and on the Galen Workman Farm in Mount Vernon. Most of the town was well littered with granite boulders of various sizes that the early settlers, down to this century, used to build fences with and, after splitting the larger ones, for roughly finished stones for house and barn foundations. The last people who could do this stone splitting in this town seem to have been John Damren (18 – 19), and his son, Leslie Damren (18). They cut the stone at the turn of the century for their mill dam near Great Pond on the Mill Stream near the Richard Damren residence. They cut the stone for the cellar rollway at the Look residence in North Belgrade, when the farm and house were owned by Harry Alexander (187 – 195), at the turn of the century. They would drill holes in the large field boulders, set in iron pins in a series and crack off a rectangular shaped piece six or eight feet long. Before cement this was the standard foundation for Belgrade barns and houses. The compiler has found a number of these boulders with the iron wedges still in place with no piece split off.

When we commenced to build town roads for automobiles in the 1920s, we used for base rock the granite stone on the stone walls beside the roads that had been taken from the nearby fields, so that most of these fine craft works cannot now be seen from the road itself. Only by going back off the road can you find them. Great granite boulder wall building work can be seen in its original condition on the top of Vienna Mountain, on Hoyt’s Island and many other off-road places. After 1880 probably very few stone walls were ever built in Belgrade. Barbed wire at that time came into fashion to replace stone and cedar rails. Granite had its day here from 1780 to 1880. In the 1920s it was used as road base; the larger boulders were sometimes put into rock crushers. At one time down to 15 years ago there was a balancing granite rock on the top shoulder of Mount Philip, left there by the passage of the glacier 10,000 years before; some boys got behind it and pushed this interesting remain off the mountain years ago. A number of these balancing boulders can be found on the top ledge of Tumbledown Mountain in the Mount Blue range.

They are the signs left of a great natural hand of the deep ice stream that once covered this land. Signs of the undersea submergence can be found in this town in the Cook gravel pit on Horse Point. Here there is a clay layer to be seen. Geology Professor Lougee in the 1930s used to bring his Colby students out to the pit to dig around in the clay and expose seashells. This was interestingly observed by the owner of the pit, Ernest “Buster” Cook, a graduate of Belgrade High School in the time of Principal Dow in the 1920s. The long-remembered Dow was reading law at the time he was here, and became a lawyer in his hometown of Norway, Maine.

*These website images are allowed for noncommercial reuse with acknowledgment.